DNA Polymerase Project

Thalia Matos - Mubassera Subah - Ethan Hicks

Exploring PDB Structure 2O8B

A collaborative effort by Ethan, Thalia, and Mubassera to visualize and annotate a key polymerase enzyme. Scroll to learn more about how the structure supports DNA replication and the experimental insights we discovered while studying it.

DNA Polymerase Viewer (PDB 2O8B)

Below is the fully formed, quaternary structure of the Mismatch Repair (MMR) protein MSH2/MSH6. Mutations on the DNA that encode this protein can lead to Lynch Syndrome, a hereditary form of colorectal cancer. Mutations in the folding of the protein also contribute to Lynch Syndrome. When we talk about and discuss these mutations, we are referring to specific amino acid changes in the protein, which affects the structure as a whole.

It is important to note the difference between the mutation on the protein, and the use/function of the protein. The complex works to ensure that pieces of DNA are replicated accurately, and that any mutations are caught and repaired. Mutations on the protein itself can lead to Lynch Syndrome (which does affect the job it performs).

Subunit Analysis

MSH2 (Chain A)

MSH6 (Chain B)

It is the combination of these two subunits that allows the complex to perform MMR.

Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer

Background

Lynch syndrome, previously known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is the most common inherited form of colorectal cancer (CRC), affecting more than one million people in the United States[1]MD Anderson Cancer Center. It results from harmful germline mutations in one of the four DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes—MLH1, MSH2 (or EPCAM deletions affecting MSH2), MSH6, or PMS2. Among these, mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 account for over half of all confirmed cases[2]citation needed. Individuals with Lynch syndrome have substantially elevated cancer risks: depending on the specific MMR gene involved, the lifetime risk of CRC can approach 60 - 80% for men, and 40 - 60% for women, and risks for additional cancers, including endometrial, ovarian, urinary tract, and several gastrointestinal cancers are also significantly increased[3]MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Lynch syndrome “mutation-positive” refers to individuals who carry a pathogenic germline MMR gene alteration confirmed through clinical genetic testing. We also classify a related group as having “mutation-negative” Lynch syndrome, or Lynch-like syndrome. These individuals meet clinical criteria for Lynch syndrome, present with non-sporadic MSI-high tumors (demonstrating microsatellite instability but without MLH1 promoter hypermethylation or a BRAF mutation), yet have either negative, inconclusive, or likely benign results on genetic testing or they may have declined genetic testing altogether.

Although they lack an identifiable pathogenic variant, individuals with Lynch-like syndrome require close clinical monitoring due to their elevated cancer risk. As a result, they typically undergo intensified surveillance, which often includes annual or semiannual colonoscopy as well as additional screening based on personal and family history.

References

- [1]MD Anderson Cancer Centerhttps://www.mdanderson.org/cancerwise/qa-understanding-and-managing-lynch-syndrome.h00-158589789.html

- [2]citation needed

- [3]MD Anderson Cancer Centerhttps://www.mdanderson.org/cancerwise/qa-understanding-and-managing-lynch-syndrome.h00-158589789.html

Failure

Which Mutations Causes Lynch Syndrome?

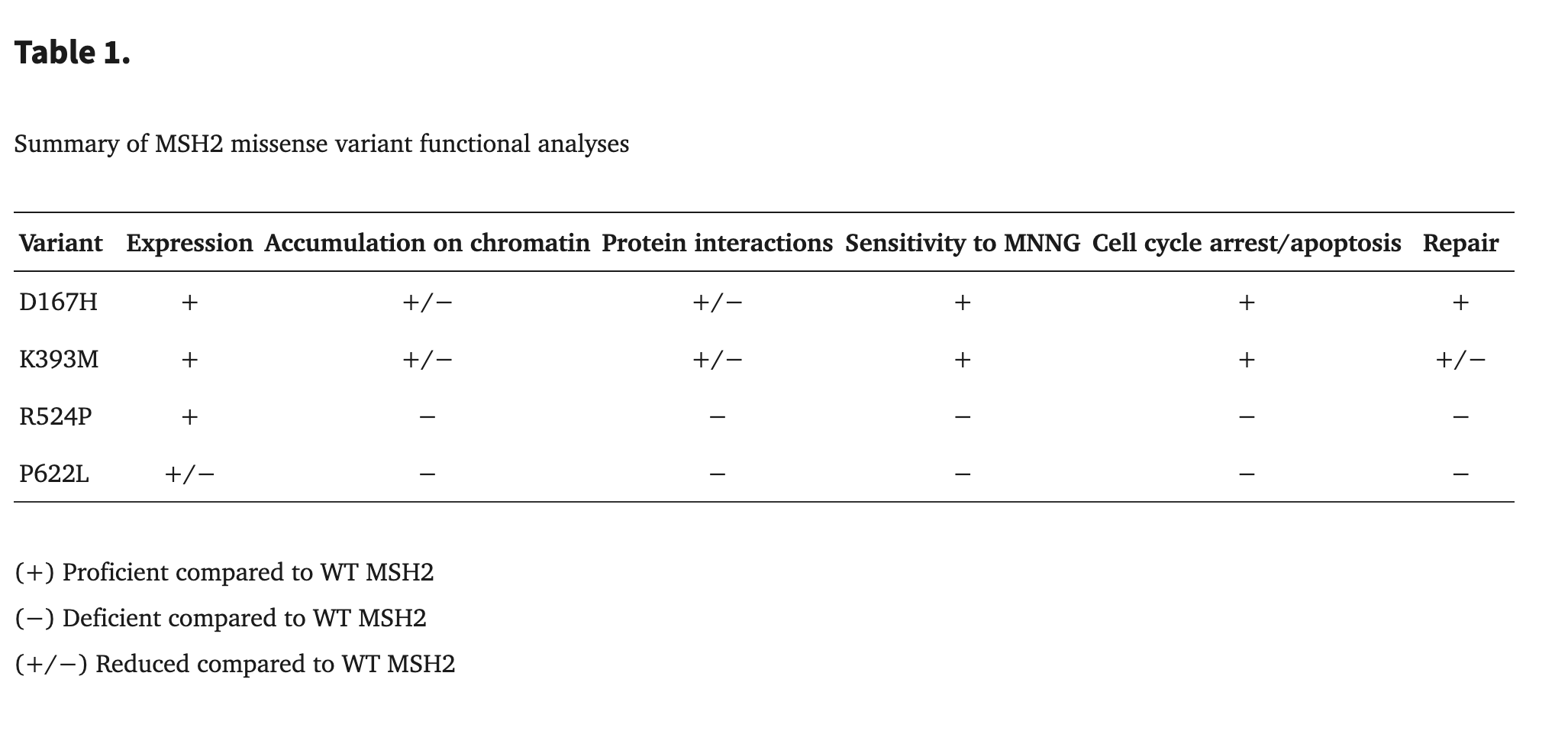

In Lynch syndrome, many pathogenic variants arise from mutations in DNA mismatch-repair proteins such as MSH2 and MSH6, and these mutations often impair function by destabilizing protein structure. Mutations that alter the chemical nature of amino acids can significantly disrupt protein stability. When a polar amino acid is replaced with a nonpolar one, the local environment loses important hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors, weakening interactions that help the protein fold correctly. Similarly, glycine or proline substitutions often destabilize secondary structures; glycine's flexibility and proline's rigid ring frequently distort helices and beta-strands, breaking the surrounding hydrogen-bond networks that keep these structures intact.

These disruptions can lead to local unfolding in key regions of a protein, including beta-strands, alpha-helices, and structural loops such as the P-loop. Mutations may also interfere with salt bridges—electrostatic interactions between positively charged residues (Lys, Arg) and negatively charged ones (Asp, Glu). When these stabilizing interactions are lost or altered, the protein can become less stable, misfold, or lose proper function, ultimately weakening DNA mismatch repair and contributing to the development of Lynch-associated cancers.

The MSH2 p.P622L mutation results in significantly reduced protein expression (approximately 50% of wild-type) and fails to stabilize key protein interactions with MSH3 and MSH6, preventing the mutant protein's accumulation on chromatin. Consequently, cells expressing this mutant are unable to perform DNA mismatch repair and display a lack of sensitivity to MNNG, failing to induce the necessary cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in response to DNA damage. This complete loss of repair and checkpoint signaling functions leads to the genomic instability that characterizes Lynch syndrome.[1]Lynch Syndrome-associated Mutations in MSH2 Alter DNA Repair and Checkpoint Response Functions In Vivo.

Proline (Reference)

Leucine (Variant)

As we can see, whether or not a mutation exists, does not necessarily mean that even has an increased risk of developing cancer.

References

- [1]Lynch Syndrome-associated Mutations in MSH2 Alter DNA Repair and Checkpoint Response Functions In Vivohttps://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2947597/

Science

MMR Proteins, Functions, and Cancer

Our cells contain a built-in “proofreading” mechanism that corrects mistakes made during DNA replication. This is called the Mismatch Repair (MMR) system. In this case, the MMR genes include: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM (deletions in EPCAM affect MSH2 expression). These proteins work together in pairs to scan DNA, identify mismatched bases, and fix them. In this project, we focused on SMH 2 and SMH 6.

In this case, cancer develops through a “second hit” of MMR mismatch, as the working copy of the MMR gene in a particular cell becomes inactivated (due to somatic mutation). As a result, that cell loses mismatch repair ability. This causes DNA errors to accumulate rapidly, especially in short repetitive regions called microsatellites. The majority of Lynch syndrome (LS)-related cancers are characterized by mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) and high microsatellite instability (MSI-H). Microsatellite Instability (MSI-H) is a hallmark of Lynch syndrome cancers indicating Indicate defective mismatch repair (dMMR). The dMMR/MSI-H molecular phenotype is characterized by an exceptionally high tumor mutation burden, driven by numerous small insertion-deletion frameshift mutations (1-4 bp) and single-nucleotide missense mutations, which collectively lead to the formation of novel tumor-associated proteins.

References

- [1]Lynch HT, Snyder CL, Shaw TG, Heinen CD, Hitchins MP. Milestones of Lynch syndrome: 1895-2015. Nat Rev Cancer 2015;15(3):181-94.

Mechanisms

NSAID Surpression of Cyclooxygenase

Currently, there are two pharmacological agents that have been shown to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome patients: Aspirin and Naproxen. NSAIDs like Aleve (Naproxen) and Aspirin help reduce inflammation and may lower the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC), especially in Lynch syndrome. Their effect is tied to how they block cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, especially COX-2.

COX enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2) make prostaglandins (PGs), which are molecules involved in inflammation and cell growth.

- COX-1 is always active and handles normal body functions (“housekeeping” prostaglandins).

- COX-2 is normally turned off, but becomes highly active during inflammation and cancer. COX-2 is over-expressed in ~85% of colorectal cancers and ~50% of adenomas.

One of the prostaglandins produced, PGE2, promotes:

- Inflammation

- Tumor growth

- Blood vessel formation

- Suppression of the immune system

- Prevention of cell death

Treatment

Current Clinical Approaches

Aspirin and Naproxen

Aspirin

Aspirin has been found to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome patients, by a study of 861 people, where 427 of them were assigned to take 600mg of aspirin per day, and 434 were assigned to take a placebo. The study went on for 2 years, with another 2 years as optional follow up. The cumulative incidence of colorectal cancer dropped by about 15% for between those taking the placebo, and those taking aspirin after 20 years. [1]Cancer prevention with aspirin in hereditary colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome), 10-year follow-up and registry-based 20-year data in the CAPP2 study: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial

Wishing we had a better understanding as to why aspirin is so effective, but sadly we do not. The above study indicates just that it is effective in reducing risk. This project has given an example of three mutations in the MSH2 protein, but as Lynch Syndrome is a class of mutations on the MutSAlpha protein, any one drug may be effected for a subsect of mutations, and invalid in others.

Naproxen

The main pathophysiology of Naproxen is that it promotes T cell proluferation in the colonic mucosa, and activates proliferation of resident cytotocix lymphocytes in the colonic mucosa. From this proliferation of T cells, it appears that the main mechanism of activation is through the increase of an immune response in the colonic mucosa. However, this is speculation, and the article mentions that mecahnistic studies are lacking.[2]Naproxen chemoprevention induces proliferation of cytotoxic lymphocytes in Lynch Syndrome colorectal mucosa

References

- [1]Cancer prevention with aspirin in hereditary colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome), 10-year follow-up and registry-based 20-year data in the CAPP2 study: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trialhttps://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2820%2930366-4/fulltext

- [2]Naproxen chemoprevention induces proliferation of cytotoxic lymphocytes in Lynch Syndrome colorectal mucosahttps://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10189148/

- [3]Mayo Clinic Lynch Syndromehttps://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lynch-syndrome/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20374719

Prognosis

Risk outlook with surveillance

Early diagnosis paired with routine screening dramatically reduces mortality. Localized tumors often carry a five-year survival rate above 90% when detected before metastasis.

Genetic counseling helps families understand inherited risk, document variants, and enroll in surveillance programs. Informed monitoring remains the key to improving long-term outcomes.